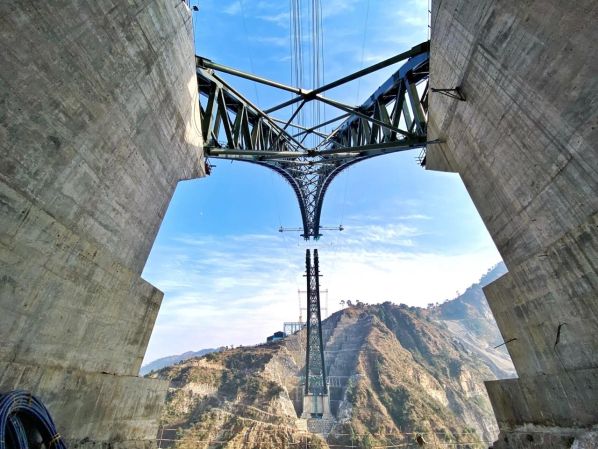

IN literature and oration, the Himalayas are an oft-used metaphor for something that is insurmountable, challenging, and uncompromising. From the inception of the 359m-high Chenab Bridge - located in the Himalayan foothills and part of a 111km railway network being built by India’s Konkan Railway from Katra to Banihal - it was clear that success would lie in the project team’s approach to the mythical surroundings. In order to successfully build the highest arch bridge in the world in one of its most challenging regions, the team would have to walk a fine line between matching the strength and grandeur of the region, and humbly acknowledging and addressing the frailties of human construction in the face of nature’s unpredictability - most notably, the massive geological drifts for which this part of the Himalayas is renowned.

Cowi has a long history of working as an independent consultant on some of the world’s greatest infrastructure challenges - from bridges and railways, to solar and windfarms, and sustainable urban development. Yet this project - arguably the most challenging civil-engineering railway project in India’s history - presents multiple interesting nuances and opportunities for problem-solving. Landslides were a constant risk. Steel elements needed to be pieced together seamlessly, so the quality of workmanship and on-site fabrication had to be of the highest standards. The bridge is also located near an area of India where there are disputed territories, with relations fluctuating over the years as the project played out. Not to mention the transport challenges - with everything from labour to tools to steel needing to be imported to a remote, previously inaccessible location.

The challenges were quite substantial given the heavily faulted nature of the site. The first stage was the selection of the most appropriate structural form for the geology on the site, which was clearly an arch. The second was to assemble a design and review team with intimate knowledge of the geology and to have them working closely together through all stages of the project. The third was that the government took on the geotechnical risk which allowed the best outcome to be pursued without commercial pressures interfering.

The client took on the supervision role and had independent inspectors on site. Afcons, the contractor, placed a very strong team on site with some highly experienced steelwork engineers who were single-minded in their pursuit of quality. All temporary staging works were made to the same high standard as the permanent works, including the fatigue inspection regime, to emphasise that all steelworks had to be of the highest quality and there would be no letting up. Finally, the client instructed regular inspections from Cowi of the bridge fabrication and Aecom for the rock slopes to ensure that the highest international standards were pursued.

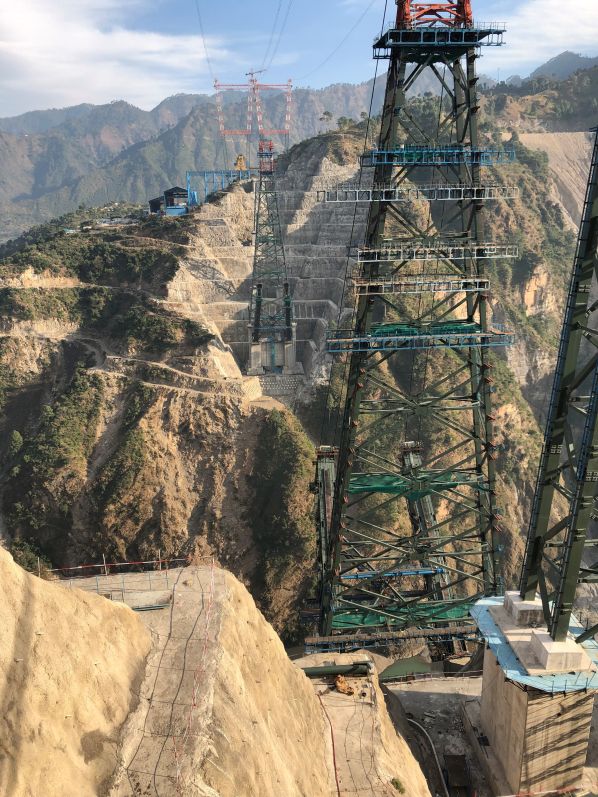

Only once you visit the site, as I have been lucky to do so many times in my role as CowiI's leader on the project, does the enormity of this task strike you. It was always a complex and tiring journey - flying to Delhi, then to Jammu, then sitting in the back of a four-wheel-drive for four hours to finally reach base camp. It is difficult to fathom the energy, manpower and logistics involved to transport over 28,000 tonnes of steel there. The on-site geotechnical engineers and geologists need to understand the natural landscape like the backs of their hands; working with it in some ways, bending it to their will in others. Roads were cut into the slopes of precarious mountain rock to improve access. A special overhead gantry crane was built to transport equipment from one side of the site to the other for efficiency.

The logistical challenges of transporting people and tools to the site required cooperation between government departments to ensure the access roads were built to accommodate the large transporter vehicles that shipped the raw materials to site. The challenge was helped by developing all the fabrication processes on site so that simple components such as plain steel plates were brought to site that were easier to ship. Local businesses developed to supply materials, local infrastructure and labour to assist Afcons in building the bridge.

For over a decade, Cowi has worked closely with India’s Konkan Railway, cross-checking their plans and construction processes to ensure compliance with global building standards, improve efficiency, and smooth out any issues. The completed bridge must be resilient in the face of high winds, earthquakes, temperature extremes, and landslides. In such a challenging region, with so many variables, the fate of the bridge is fully dependent on the determination and flexibility of the project team and workforce involved.

It was with great awe, admiration and pride that, in April this year, I watched from a video link in my house in Britain as the monolithic steel arch of one of the most unlikely bridges you could imagine was officially completed. The atmosphere was exalted, befitting its surroundings. Here, in the middle of the mountains, in a country not known for its steel bridges, a record-breaking structure had been created, all due to the professionalism and problem-solving ability of a dedicated team led by the untiring efforts of the chief engineer, Mr R K Singh.

Beyond the many individual feats of engineering involved, both big and small, the construction process itself has had several wider positive impacts on local communities. The improvement of the transport network to get to the remote site has allowed associated industries to grow, creating opportunities for trade, supporting the influx of new technology, and improving the quality of education and healthcare for local communities.

But the work is not yet over. The flickering lights of hillside village encampments remain on, and the arch remains un-decked - a single arched eyebrow, curiously awaiting completion. Another year lies ahead of us before we can join Mr Singh and sign our names to the Chenab Bridge - point to it and tell our kids and grandkids: “I helped build that.” But, from the beginning, the creation of a monument like the Chenab Bridge has in many ways been a self-fulfilling prophecy; far from being deterred, all involved have steadfastly committed over a decade of work for the anticipated pride of completion.

At Cowi we are thrilled to learn time and again that, with sufficient creativity, dedication and attention to detail, humans can achieve some pretty impressive things. Rather than a triumph over nature, the Chenab Bridge is a triumph of the ingenuity of man with nature - as a source of inspiration, juxtaposition and foundation. This unique union has resulted in an awe-inspiring structure that will be marvelled at for decades to come when it opens in 2022. IRJ