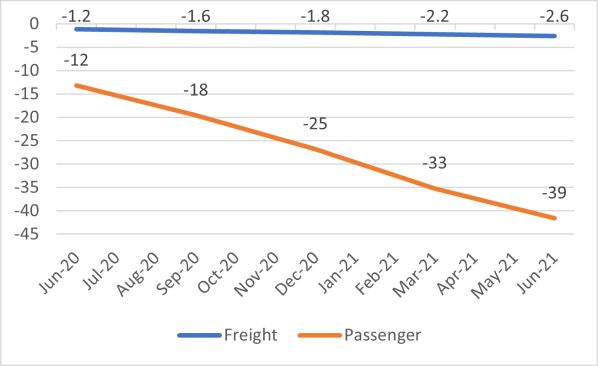

EUROPEAN freight and passenger operators and infrastructure managers across Europe lost an estimated €50bn in revenue during the Covid-19 pandemic between March 2020 and the end of 2021, according to the Community of European Railways (CER).

CER launched the Covid impact tracker at the beginning of the pandemic to aggregate the impact on the sector, with the results showing just how severely the loss of passengers and freight has been felt. The trends seen in the tracker are more or less in line with the waves of the pandemic, says CER executive director, Mr Alberto Mazzola.

“We’ve seen heavy losses at the beginning where there were severe lockdowns,” he says. “Then we got to the summer when the situation improved, and then it went back down again in the winter. We have seen the first effect of vaccines, that traffic increased. We can project by the end of [2021] to have lost about €50bn in revenue.” (Table 1).

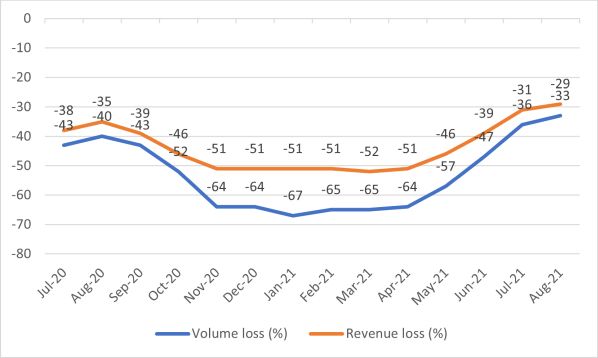

Around 90% of these losses have been registered in the passenger sector. Revenue in the first half of 2020 was down 40% compared with 2019, dropping even further in the second half of the year to 43% and 41% for the full year (Table 2). The situation worsened at the start of 2021, dropping to 51% for the first quarter of the year compared with 2019, before recovering slightly to 45% lower in the second quarter. Signs have also been promising since then, with July and August at 31% and 29% respectively.

The fall and recovery of revenue inevitably largely followed passenger numbers, with passenger-km down 46% in the first half of 2020 and 51% for the second half of 2020, down a total of 49% for the full year. This dropped further to 66% in the first quarter of 2021 before recovering slightly to 56% in the second quarter of the year. Signs were again looking positive towards the third quarter, with volumes down 36% and 33% in July and August respectively.

Mazzola says that of the three main passenger rail sectors - commuter, long-distance and cross-border - the smaller cross-border segment was hit the hardest, while long-distance was also badly affected with commuter rail less affected.

Mazzola says this is because most commuter rail services are provided under public service obligation contracts, while long-distance rail is usually operated on a commercial basis.

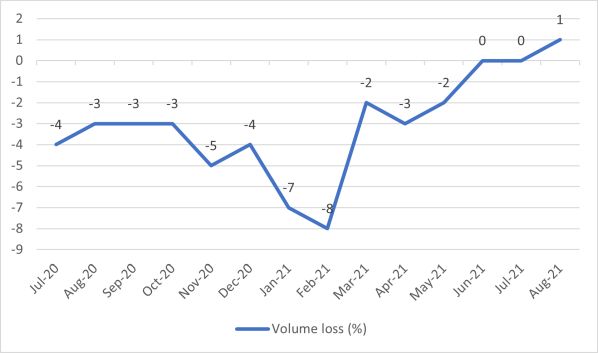

While not as heavily affected as passenger rail, rail freight operators have still recorded between €3bn and €4bn in lost revenue over the course of the pandemic. Revenue was down 14% in the first half of 2020 (Table 3), recovering slightly to a 12% deficit for the full year. It then remained at 13% for the first quarter of 2021, and 10% for the second quarter.

Mazzola says that while the figures are not as bad as for passenger rail, the very tight margins that rail freight operates under means that these losses in revenue will come through as losses on the final balance sheet. As rail freight is also run on a commercial basis, it has also been more difficult to secure financial aid.

“If you’re losing money and it’s your business, that’s your responsibility,” he says. “It was important to have these data because they helped to convince the European Commission (EC) about the reduction of track access charges, so that at least in terms of a reduction in cost the reduction in revenues can be partially compensated.”

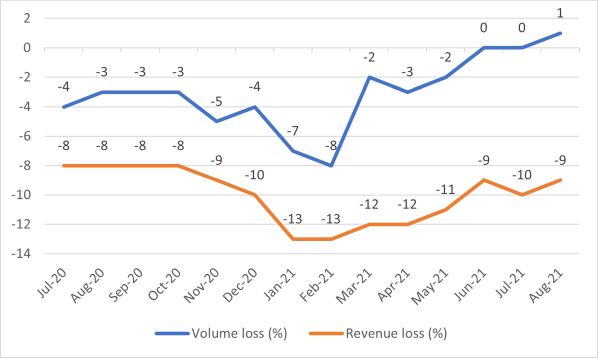

Combined with fewer trains operating, this reduction of track access charges had a knock-on effect on the revenue recorded by infrastructure managers (Table 4). Revenue for the first half of 2020 was down 13%, recovering slightly to 8% for the full year. It was down 6% in the first quarter of 2021, and only down 2% for the second quarter.

“But the reduction in the number of trains is not equivalent to the reduction in the number of passengers,” Mazzola says. “The commission is also tracking what is going on, but what they’re tracking is the number of trains. If you have 100% of trains with 50% of passengers, but you count only the number of trains, you have the impression that everything’s going fine while the company is losing 50% of its business.”

Mazzola says this is why it has been so important to keep the records. CER began sharing information on tools and techniques such as how to properly sanitise the trains at the start of the pandemic, but soon realised it was also important to share the data on how badly the sector was affected. The data has subsequently been used by CER during consultations with the European Commission and other European institutions, as well as individual railways during discussions with governments.

“It’s a positive sign that public authorities are investing more in rail infrastructure because this will help us develop our business, which was a bit difficult in the past.”

Alberto Mazzola, CER executive director

“If there is the correct information, then you can develop policies, but without this information it would have been a bit difficult to promote policies to reduce the impact,” Mazzola says. “We also realised that we could not go on without any intervention, including public intervention. And to support this public intervention, to make the best decision possible that information was needed.”

The information was collated by Mazzola and CER head of rail freight services, Mr Jacques Dirand.

“We are treating the information we receive from the different members confidentially,” Mazzola says. “We don’t provide to anyone the source of the information unless it is anonymised. We can provide different railway undertaking’s results but in an anonymous way in terms of a percentage, and we provide the overall results to everybody.”

Compensation

These losses have been partially offset through compensation from national governments, but Mazzola says this only amounted to around €10bn, which was much less than received by other modes such as air travel, which suffered similar losses.

Mazzola says this issue was raised with DG Competition, pointing out that the guidelines concerning state aid to support the recovery from Covid-19 didn’t give any consideration to whether a company is green or brown under the European Union’s Green Deal.

“What we are claiming is that in the future these guidelines for state aid for Covid, as well as general guidelines for state aid, should include more green aspects,” Mazzola says. “Aviation received much more support than rail, particularly in long distance international traffic. If you want to pursue a green deal policy and show support for greener transport compared with brown transport, it should have been the opposite. I’m not saying that you could not support aviation, just to be clear. Aviation is also suffering a lot of losses. But since there is also a policy to become greener and reduce CO₂ emissions, we have part of the business where rail is definitely better.”

Mazzola believes that air received more support than rail, despite the latter being a much more sustainable mode of transport, because there was an impression that rail was more resilient. While aircraft were grounded, most trains were still running albeit with fewer passengers on board, which made it look as though rail revenues were holding up more than they were.

“But it’s an important point to realise that we are also facing consequences. And these things must be corrected. We will have difficulties to invest in the future. And these difficulties are the opposite of the policies that we would like to pursue. If you register losses, your capital is reduced, your equity is reduced and debt is increased. And certainly, you will reduce future investment, at least on rolling stock and so on. These will be consequences in the future unless these things are corrected.”

Dirand says it is a balance between trying to please all sectors or keeping the objectives of the green deal in mind.

“There are industries that are going to be frustrated, but this is the consequence of the policy choices that you make,” he says. “There are some industries that have to be more fairly compensated and others where the choices are going to be a bit more difficult.”

Outlook

This year is again expected to be difficult, Mazzola says, with the most optimistic view that operators may return to pre-covid passenger numbers in 2023 at the earliest. The recovery of freight will depend on new industrial policies, changes in supply chains and trade, as well as the expected momentum from greener policies.

But medium to long term, there is cause for optimism with investment in rail infrastructure featuring strongly in many of the Covid recovery funds outlined by countries across Europe. Rail will receive €46bn through the 15 national Covid-19 recovery and resilience fund plans that have been released so far.

“It’s a positive sign that public authorities are investing more in rail infrastructure because this will help us develop our business, which was a bit difficult in the past,” Mazzola says. “It’s an important point that we are registering investments. Covid numbers are very negative but we have hope, and we are registering this trust in railways by decision makers in making more investment in that.”

Mazzola says both freight and passenger rail have been resilient throughout the pandemic, with 95% of passenger trains still running and freight able to continue carrying goods cross-border during lockdowns that prevented trucks from carrying freight on the roads.

“This is something that we need to reflect on because everybody is now thinking that was such a huge crisis, so what lessons can we take?” he says. “Resiliency is an important one, and I think we’re the most resilient mode.”