PUBLIC transport ticketing has come a long way over the last 30 years, moving from paper tickets, to magnetic stripe and more recently smart cards, and near-field-communication (NFC) enabled mobile phones. However, these are usually in the form of proprietary schemes developed by a single supplier within a closed network, which require considerable capital investment and have substantial operating costs.

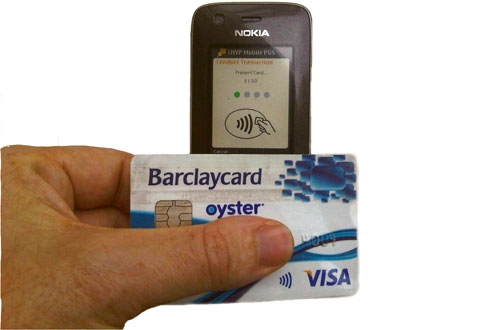

As technology has developed in other sectors, most noticeably through mobile communications and the switch to contactless cards in the banking industry, opportunities are opening up for rail operators to make fare collection more convenient for users and cheaper to run. They also offer new ways of collecting revenue, breaking away from traditional ticketing methods and their inherent constraints.

By moving to an open payment model, operators would become merchants participating in a bank-led scheme rather than owners of a dedicated ticketing infrastructure. This could reduce costs through the use of off-the-shelf equipment from a range of suppliers, rather than bespoke equipment made to proprietary specifications.

Introduction of EMV (Europay, Mastercard, and Visa) schemes, the global standard for use of credit and debit cards for point of sale or ATM transactions, can dramatically change the concept of ticket purchase by offering more sophisticated facilities that take advantage of calculations being performed in the back office, rather than at the fare gate.

While some operators want to move away from smart cards becauses they are not viewed as a core business, others are keen to issue them as the registration fee generates a significant revenue stream. However, social inclusion is a key public transport objective so operators may still need to offer alternative payment methods to those who do not have contactless bank cards.

Non-transport payment applications have been cited as a benefit of introducing smart cards, but in reality there have been very few examples, as the proprietary nature of the infrastructure makes such applications costly. Moving to EMV could remove this barrier, allowing customers to use one card for all payments.

Mobile technology is widely considered as the future of payments, and while this is true to a certain extent, a mobile on its own does not have the capability to perform payments without an application to carry it out. In this area, companies such as PayPal and Google are presenting their ideas for a modern payment network that will operate in competition with EMV, the established technology of the traditional banking industry.

Contactless EMV cards, issued widely in Canada, Mexico and much of Europe, have been developed with offline capabilities, enabling the card to debit small amounts without the online authorisation usually required to guarantee that the merchant will receive the funds. This capability also reassures transit operators that they are dealing with a genuine card.

The majority of contactless EMV cards are issued supporting the highest level of dynamic data authentication. In the future, the payments schemes have also specified a data area that can be used by merchants to record where passengers might enter and exit the network using their cards. This data could then be used in the transit space for capping calculations, other payment models and revenue inspection.

Three key areas to consider when designing a new ticketing infrastructure are the scope of the network, interoperability and the likely cost savings. Urban operators have different priorities to their inter-urban or rural counterparts. Speed and self-service are essential in the urban environment, while inter-urban operators need to offer a greater range of customer-focused products and services, which might include integrating ticketing with connecting urban or rural services.

Opportunity

Utilising bank credit or debit cards, which passengers already carry and are useable worldwide, provides operators with an opportunity to develop a ticketing or payment strategy with no issuance costs. At present, transaction data, value top-ups and ticketing products cannot be stored on the card. Plans are in place to introduce payment cards that can hold transient data and will support future ticketing applications.

The operator will also be able to use the card to collect a payment at the point where passengers enter the network or sometime later. In this case, a new middle-office infrastructure records when and where the passenger enters and exits the system charging an end-of-day amount.

Another important consideration is whether the reader can operate off-line or if it needs to connect to a back-office system. Although the primary benefit of the card-based model is to operate completely offline, the reader and middle-office models may need occasional network access to pass data, including managing fraud and payment card authorisation requests.

The introduction of payment cards can substantially reduce costs. The most significant of these is the elimination of card issuance, as well as the end of dealing with issues raised around the management of a proprietary system, and the eradication of card and ticket distribution networks.

However, there will be new costs associated with interchange including the charge the schemes make for processing the payment. This is passed to the transit merchant through the acquirer, the financial institution that processes credit and debit card transactions, which are issued either directly to the card issuer, or via the Visa or Mastercard network.

Reader design is inevitably critical to the successful implementation of any project to accept new media. Poor design would increase cost through unnecessary rounds of re-certification and could affect its vulnerability to security attacks, service denial or data harvesting.

The reader will be required to support numerous applications, so the software for each one - be it card detection, payment card applications such as Visa, MasterCard, Amex, Discover, or a proprietary application - should be developed and installed separately, with an approach that's more akin to loading applications onto a mobile phone. If this is not followed, changes to one application could result in a need to retest the complete reader. Also, developers will want to minimise the number of times the reader is submitted initially and when changes are made to specifications and code due to the high cost of certification.

If the reader is, or might be, handling payment data, the implications of PCI-DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard) must be considered. Payment data cannot be held or transmitted in a format that would allow it to be intercepted in plain text form. The most secure method for securing compliance would be to encrypt all transactional data at the source before it is stored and transmitted.

Even with all this information, how can operators know that everything will work to specification, and that transactions will not take minutes instead of milliseconds? The answer is to prototype the system, and test the more complex processing that the reader must undertake. This includes activating the card and selecting the correct application, deny-list processing, and any other management processes required to meet PCI-DSS.

There are still many challenges to implement readers that are capable of accepting cards from several schemes as contactless EMV is introduced and older technologies are phased out.

Some transit operators such as Utah Transit Authority (UTA) have successfully implemented open payments and other operators such as Transport for London (TfL) are getting close to the point of implementation and will start to test their systems shortly.

As the convergence of payment methods begins, bringing together payment card schemes and transport operators, there are many institutional issues that need to be addressed. But in the long term, convergence will produce benefits for operators and their passengers. And once this has been successfully addressed, it may be time to look at the next steps and to get to grips with implementing NFC.