FOR generations, the rail industry has taken safety to heart and is justifiably proud of this. Safety engagement is one of the key means by which railroaders relate, watch out for, and protect each other. However, there are unresolved safety issues that keep perpetuating. Derailments and collisions related to infrastructure, rolling stock mechanics and human factors are common examples.

Is the railway industry going far enough in terms of safety? The digital world continuously demands integration of systems and solutions, yet it is unforgiving to incomplete, inaccurate, incongruent and incohesive requirements, specifications, designs, implementations, and operations. System safety has been in place in safety-critical industries such as defence and aviation for several decades, but it is in its infancy in the rail industry and transport supply chain.

A new perspective is required, as demands for safety are no longer satisfied with incremental extensions of existing work. Rather, innovative approaches, ranging from new safety conceptual models to solution approaches, are needed to deal with new technologies such as software and artificial intelligence (AI). A shift from traditional non-systems or piecemeal approaches to interoperable systems is required.

While railways are responsible for safeguarding and improving their safety performance, they must also follow new regulations. A new perspective on system safety is required for all members of the transport ecosystem, with a platform and philosophy for it. By using methodologies in systems and lean process engineering, as well as organisational behaviour, system safety can be embedded, with a means to reduce implementation risk, accelerate time-to-value realisation, improve safety performance, and grow cultural and capability maturity at a sustainable pace. What is more, applying entrepreneurship and business precision will enable safety to move from a cost centre to a value-added business driver.

Safety just for safety’s sake is no longer viable. Overlaying and managing digital initiatives using existing safety practices is no longer sufficient and is too much to manage. Instead, system safety will drive business cases for automation and leverage to the next level of operational effectiveness. System safety allows the compounding complexity and increasing volume and speed of change imposed on the railway industry through regulation, internal growth or competitors, to be managed from a safety perspective. As a result, customer service is provided more reliably, predictably, effectively, and safely.

Safety is an often-used term loaded with meaning and littered with ambiguities. Fundamentally, safety is the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury or loss.

System safety requires a risk-based strategy centred on identifying and analysing hazards and applying remedies using a systems-based approach. This differs from traditional safety strategies that rely on the results of accident investigations or epidemiological analysis. The systems-based approach requires the application of scientific, technical, and managerial skills to hazard identification and analysis, and elimination, control, or management of hazards throughout the life of the system. Hazard analysis is systematically done at many levels and where all levels are integrated for full end-to-end traceability.

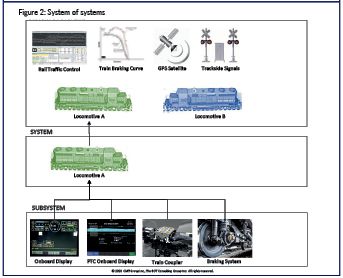

Most systems today are part of a “system of systems,” even if they are not recognised as such. In a system of systems, a collection of task-oriented or dedicated systems combines resources and capabilities to create a new, more complex system that offers more functionality and performance than the sum of its parts.

Operationally, a railway acts as a system of systems. From a development and acquisition standpoint, railways have focused on independent systems. Most transport systems were created and then evolved without explicit systems engineering at the system of systems level.

Interoperability

From a system safety perspective, considerations need to be applied at the system of systems level. When it comes to interoperability, more emphasis on system of systems is needed, given the relationships among what were previously considered independent systems.

Figure 1 shows simplified system relationships. Each system, such as a locomotive, signal, or GPS satellite, must not only operate individually but must also interface with each other or be interoperable with other systems. To achieve an acceptable level of safe interoperability, such systems must be engineered for safe operation and evaluated in the system of system context. The same philosophy applies to subsystems constituting a system. For example, a faulty coupler failing to engage on a wagon could result in a train system separation, which at the subsystem or train system level is not an immediate safety concern. However, in the system of system context, the effect of the coupler failing to engage if the train is climbing a gradient, the emergency brake is absent, or associated rail procedural mitigations fail could be a collision or derailment.

The system safety goal is to eliminate or reduce the probability of mishaps at various levels between elements, subsystem, system, and system of systems. When two systems, for example Locomotive A and Locomotive B (Figure 1), operate on the same line, it is the operator’s duty to maintain adequate train separation. Similarly, it is the obligation of each system and subsystem supplier to ensure that their system or portion incorporates fail-safe design methods to ensure that acceptable levels of safety are part of the system design.

A new perspective on system safety is required for all members of the transport ecosystem.

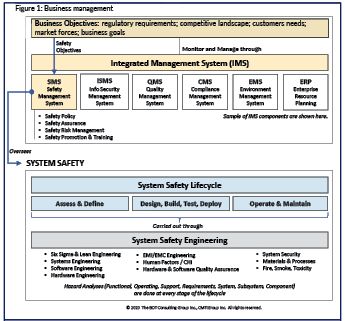

Figure 2 lays out a holistic view of safety. This universal model can be applied to a company or business unit, and across companies and partnerships.

From a business management perspective, safety objectives are defined by regulatory requirements, and shaped by various inputs such as customer needs, market forces and business goals. In Figure 2, the Safety Management System (SMS) is the platform for monitoring and managing the performance of safety objectives. Typically, companies, business units, or ecosystems with greater integration of management practices would also have an Integrated Management System (Figure 2). Rather than having individual management systems operating in silos, the company can be managed more effectively using joined-up thinking, better aligned business objectives and KPIs, and simpler audit models. System safety performance is overseen by the SMS.

Even though regulators establish safety minimums, railways are working innovatively on piecemeal safety measures such as autonomous track inspection, PTC and ERTMS to improve safety, while individual railways lobby regulators for exceptions and trials. Nonetheless, there is an opportunity to enhance safety on all fronts.

Railways are in the initial stages of comprehensive system safety management, as mandated by regulators. While SMS is the primary focus, we caution railways not to rely solely on SMS for safety risk management, as it can provide a false sense of security.

System safety as a functional discipline is incomplete in the railway industry.

As advanced technology becomes increasingly prevalent, the urgency to integrate it into systems increases. However, the integration of new technologies with existing layered solutions, including safety measures, becomes tricky. With the rapid speed of change, the influx of new things to learn and the unrelenting pressure to deliver more with less, current safety practices can become inadequate often resulting in incomplete and not fully integrated safety solutions.

Even though safety is a primary priority, it needs more support in business plans. The temptation to implement reactive fixes compounds the safety conundrum and adds confusion. Safety must be designed upfront and built into all layers of hardware, software, systems, and processes including operations.

These collaborations must include operators such as traffic controllers, drivers and track maintainers, and system safety practitioners such as system safety engineers jointly identifying safety-related operations and improvements as well as operational safety constraints.

Railways must also work closely with their suppliers and contractors to ensure that the products and services they purchase meet system safety requirements when integrated into their own systems and operations. Safety improvements become derived safety functions for existing or newly defined systems. Safety functions replace existing procedural mitigation to achieve greater safety and reduce operator workload.

To prevent introducing safety-significant anomalies in transport systems, the system safety approach is the surest and lowest-risk path. Traditional safety approaches alone no longer meet the new demand.