“TRANSPORT is designed by men, for men, but we know that women rely on public transport much more than men do,” says Ms Lindsey Mancini, head of the secretary general’s office with the International Association of Public Transport (UITP).

“The majority of our customers are women, the majority of the trips made are made by women, and the experience of women on public transport is different from men. The reasons to travel also tend to be different from men. That is why we need to have more women in the workforce.”

The Women in Rail autonomous agreement, set to be adopted through a vote by the European Transport Workers Federation (ETF) on October 27, seeks to address the problem of gender representation in the sector. The Community of European Railways and Infrastructure Companies (CER), which represents employers in the rail sector, adopted the agreement during its 68th General Assembly on September 20. A provisional agreement was reached on June 30 in the final round of negotiations at EU level for a binding agreement aimed at promoting the employment of more women in the sector.

“This is a particularly positive signal in the European Year of Rail and a strong sign for cooperation between the social partners,” CER chair and CEO of Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB), Mr Andreas Matthä, said when the agreement was adopted. “The agreement takes up current challenges, sets ambitious goals and sets an example for other sectors. I am aware that the implementation will also pose challenges. However, the railway sector needs to function as a pioneer to safeguard the attractiveness of railways as an employer also for the future.”

“By improving the roles for women in companies, you end up improving the situation for everyone.”

Lindsey Mancini, UITP

“To my knowledge, this is the only agreement in the social dialogue between employers and trade unions that is taking place this year,” CER executive director Mr Alberto Mazzola told IRJ. “I mean, industry, shipping, any kinds of health care, no one is having an agreement at European level.” Asked why this is the case, he points to the work going on for the past three years in the lead up to the signing of the agreement combined with the desire to finalise it in the European Year of Rail.

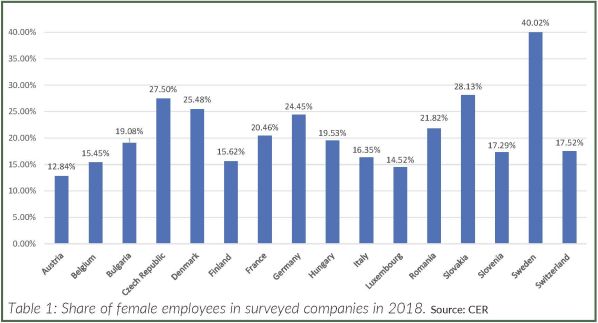

Men continue to dominate rail industry employment. Figures from a CER report show that the average share of women in 2017-2018 in the EU was 21.4%. According to the UITP, this figure remains roughly the same in 2021 - certainly, there has been no upward change.

This also represents a failure to meet a target set by the ETF and UITP in 2014 for women to account for 25% of the workforce in Europe by 2020. This was described as ambitious at the time. Yet, while rail’s figure may seem low, it is actually around the same as other modes of transport. In the aviation and road sectors, the figure is 22%.

Career culture

There are many reasons why women either do not believe the rail industry is an acceptable career path, or if they do join, why they do not stay for very long.

Culture is key. Ms Tracey Barber, group HR manager for XRail Group, who works across Europe and the Middle East, says that not enough is being done at an early age to enable young girls to at least consider rail as a career. “We need to interact early,” she says. “Go back to when you were four, five or six and the police and fire service would come to your school and they would always be men. Then look at what parents do with their kids at weekends - mums will take their daughter to the hairdresser - it’s what they see. They grow up thinking they should be hairdressers, beauticians and boys should be firefighters or police.”

The parental relationship is vital. “I’m a mum,” Barber says. “The biggest influential people remain parents. My daughter wanted to be an engineer in rail and my heart soared. I knew I could get her the right people to speak to but not everybody has that. Her best friend wanted to be a doctor, but her parents said she wouldn’t make it because she was a girl. Is that bad parenting, or just being realistic?”

whether women apply for certain jobs. Photo: SZ

Perception around what is a male role and what is a women’s career remains, says Ms Brigitte Oliver, senior adviser on social affairs at UITP. She says that in many countries, you will hardly see women driving buses. “Why? There is absolutely no reason they should not be able to drive a bus,” Oliver says. “And part of the problem is that women don’t see themselves in this type of job, so it’s a cultural problem, it’s broader than just a company.” Where companies can help, Oliver says, is to show that jobs such as these are accessible for everyone.

In German-speaking countries, Oliver says that regular open days are organised regarding the recruitment of apprentices, and while they specifically seek to attract girls, there is a drive to attract families to attend. “It’s not enough to convince the girl, because if a family says no, it’s not a job for you, then nothing will happen,” Oliver says. “I think it’s a problem which is much deeper than just the culture in a company.

“I think gender stereotypes have to be addressed at the earliest possible stage in schools.”

Figures published by CER (see Table 1) show a wide range in the presence of women within the companies, from 40.2% in Sweden to 12.84% in Austria.

Barber says that in Sweden parents are legally allowed 480 days leave after the birth of their child. The Swedish government encourages each parent to take 240 days. Of those 480 days, 390 are paid at 80% salary. That, she suggests, is why there is such a high percentage of women working there compared with other countries.

The roles also vary within companies, but CER figures show that of the female workforce, only 2.9% are locomotive drivers, 21.4% work in traffic management which is a drop from 22.9% in 2017, while on-board personnel have the highest proportion of women with 37.4% of the workforce. CER says that overall, 4659 more women joined the industry between 2017 and 2018.

Mazzola agrees that reaching young people at an earlier age is one way that the disparity in representation between the roles can change. This needs to be at a secondary school he suggests, arguing that university-age is too late. “It is important that we show that these jobs can be done,” Mazzola says. “We need to show that different functions can have different people.” He is concerned about the lack of female locomotive drivers, saying this needs to increase “even though it’s a difficult job, especially if you’re working freight trains for example, where you have long hours and you’re driving at night.” The on-board personnel figure Mazzola says is “good” due to the difficulty of the role. “After the driver this is the most difficult situation,” he says, and highlights the need to be available in case cover is required.

As far as management is concerned, the representation of women varies. At the executive level, the figure is 25.3%, while in middle management it’s 21.9%. The lowest is team leaders with 18.4%. The positive is that each level recorded an increase from the previous year. CER figures show that across these management levels, the number of women increased by 206. Spanish infrastructure manager Adif has the biggest share of female executives (46.2%) followed by ÖBB (27.3%).

Mazzola believes there is a more balanced representation in boardrooms, but lower down within organisations that changes, as the ÖBB figure attests. He says there needs to be more possibilities for women to feel able to apply for the opportunities, pointing out that in his previous experiences many job candidate selection committees often feature more women than men, but most interview panels are made up entirely of men. Mancini says that without the right balance at management level it will be very difficult to change the way companies profile themselves as employers, the way they interview candidates or even the way they publish job advertisements.

“Maybe where we are starting to see improvement is in the leadership fields, because that’s one area where you can quite quickly make an impact with policy,” Mancini says. She tells IRJ that this will continue to improve as executive committees become more gender balanced. “The real problem is the grassroots.”.

Ms Soline Wholley, CER policy adviser, EU public affairs, agrees. She says recruitment processes are a key aspect of the drive for change, and there are some very simple methods that can quickly be introduced, such as having photographs of women on the company website and training recruiters to overcome an unconscious bias. “I think it’s not specific to our sector,” she says. “‘I’m going to recruit somebody who looks like me because I feel comfortable with that.’ Training them to see that there is an unconscious bias is part of the agreement.”

However, Mancini says one problem when looking at the figures, is that there is not good data when it comes to measuring gender representation in the workforce, although this is being addressed. Wholley says there is going to be an obligation of reporting and monitoring as a result of the agreement’s introduction. She says the more what works to improve gender representation is understood, the more the agreement can be improved. “This is the first step in our process and that’s why we plan on reviewing it because we’ll take stock of the figures that we have, and that will be on a more regular harmonised way.” No longer will data be voluntary, instead it will be mandatory and more structured. This, it is hoped, can lead to improved gender diversity polices.

How can the gender imbalance be tackled? As well as earlier engagement, Mazzola says revisions to the workplace culture are necessary, including smart working and a good work-life balance, and to eliminate issues such as sexual harassment.

Change is happening he suggests, but slowly. Stereotypes need to change he says, and this can be achieved by developing mentoring programmes and improving recruitment methods.

Incentives

Do companies need to incentivise tackling the gender divide, and are incentives beyond wages necessary to attract women to rail? “Transport and rail companies tend to be big employers in cities and it’s always a struggle for them to fill all the positions,” Mancini says. “There’s this whole demographic of women out there looking for jobs if only we could make sure that women see themselves in those roles.”

Balancing work with family life is critical to any remedial strategy according to Mazzola. Work is underway with unions and organisations with the aim of providing more flexibility although it is recognised that this is not always possible in every discipline.

Mancini says ideally companies should design jobs with women in mind. “We still know that women tend to bear the brunt of childminding roles, and making sure that there are shifts available that coincide better with family life makes them much more attractive to women.

“There is no quick fix. The figures don’t change from one year to the other very dramatically, so we hope that they will evolve in the right direction.”

Brigitte Oliver, UITP

“By improving the roles for women in companies, you end up improving the situation for everyone. UITP has a Diversity and Inclusion working group and its members tend to be those who are more forward thinking when it comes to such issues. There is a diversity manager whose role is to look at the issues raised, and when the group convenes best practice is shared along with various tips to try to raise awareness.”

The younger generation offers hope for Wholley because they do not necessarily see a job specifically for a boy or a girl. An example she cites is the train driver of the final leg of the Connecting Europe Express from Strasbourg - Paris who told CER that driving trains was always her dream because of the responsibility it offered along with the travel opportunities.

Positive discrimination and quotas are mentioned when industries look to understand why there are diversity issues. Mancini understands this but says that no UITP members are engaging in such a practice. “One way to try and improve numbers without going too far is that your interview shortlist can be more balanced,” she says. “After that then it’s about the best person for the job, but at least companies are then making sure that women are getting in a position so that they can sell their credentials.” This approach could also show that not enough applications are being received from women, which would allow companies to take on Mancini’s point about how or where jobs are advertised.

very few working as locomotive drivers. Photo: Deutsche Bahn AG/Oliver Lang

CER is no longer setting targets regarding what percentage of the workforce should be women by a certain date. Instead, it wants to focus on tackling the issue.

UITP has set a target of 40% female representation by 2035. But this raises the question of how that figure is achieved?

“There is no quick fix,” Oliver explains. “The figures don’t change from one year to the other very dramatically, so we hope that they will evolve in the right direction.”

Mancini understands that there needs to be more action, but says that by talking about the issue more, the unconscious bias can be reduced. “Unfortunately, we need to have a lot of talk going on,” she admits. The Women in Rail autonomous agreement is a step in the right direction towards tackling gender imbalance in the rail sector. It will come into effect after the formal ceremony on November 5, after which it will take around a year to implement. In 2024 progress will be reviewed. Hopefully the next three years will show just how seriously the sector is taking the issue.