“OK” is an apt description for the performance of the US rail freight sector in 2022. After 48 weeks of the year, overall growth of wagonload freight volumes was anaemic at 0.2% compared with 2021. The targeted higher growth intermodal market stumbled badly at -3.7% as of early December. And of the seven major Class 1s, only a few reported significant traffic volume or market share gains.

A takeaway from this result is that the precision scheduled railway business model did not deliver the expected market growth gains that management was seeking, with several factors at play here:

- a shortage of train crews after too many of the railways cut their worker pools too far and lacked sufficient reserves when the markets started to recover

- a shortage of locomotive power, which resulted in

- poor terminal dwell times and lower train speeds.

Promised higher-quality performance deteriorated in many cases to less than the delivered service in the pre-pandemic year 2019. Indeed, for much of 2022, using a four-week average wagonloading metric, the US Class 1 wagonloading volume was lower than every year since 2008 apart from the crisis years of 2009 and 2020. As 2022 closes, volumes are below those reported in 2009.

Again, these are overall numbers. Several railways are showing better improvement relative to 2021. Shortages of crews may continue to improve into the first half of 2023. Furthermore, a few carriers - Norfolk Southern (NS) being one - have announced that they are changing their business model to be more customer-centric and return-on-investment oriented instead of operating ratio focused.

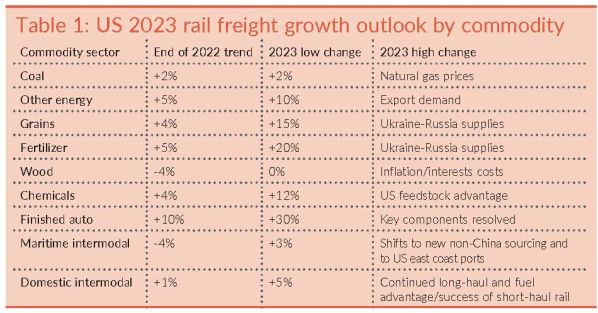

As we look ahead to 2023, the following forecasts are not specific to a certain carrier or railway. Rather, the focus is on the various freight segments that broadly make up the tonnes and tonne-km recorded on the North American network. I will concentrate on volumes and the various markets served and not on company revenue or profit targets to offer a forecast of what the likely year-on-year change in specific commodity groups will be, at both the high and low end of the range.

The first approach is to consider overall traffic growth, beginning in Mexico. Increased automotive production for the North American market should support growing intermodal traffic to and from the main export gateways at Laredo and El Paso in Texas. Grain and fertiliser imports from the United States and Canada are very likely throughout 2023. The volume increase in fertiliser imports is likely to be highly dependent on market prices; expect to see very significant increases in the price of fertiliser and petrochemicals, which might dampen the ability to buy.

In Canada, I expect the railways to be handling high export volumes of grain and other natural resources throughout 2023, as well as fertiliser. This may be offset by possible declines in wood products and intermodal volumes of general merchandise as global economies respond to both inflationary and recessionary economic forces. In the automotive sector, we should also expect a rebound in finished cars as manufacturers catch up with the backlog caused by shortages of computer chips and other parts over the past two years.

With the economy showing mixed strengths and weaknesses as 2022 ends, it is prudent to expect a year-on-year decline in total freight volumes moved in the United States in both the first and second quarters of 2023. But, against this background, there should be strong growth in grain, chemicals, food and energy, as well as gravel and stone driven by market demand stoked by infrastructure projects that received federal funding in 2022.

Considering international intermodal traffic, the growth in the volume of containers moving by rail should pause and then recover relative to 2022, and 2023 might even see a volume base similar to that last seen in 2019. This will in part be due to rate competition from road haulage in the medium and long-distance markets. Many trucks on the US highway network are of the semi-trailer type, and this business is not easily transferred to rail unless both the shipper and the end customer shift to using domestic containers. Rail can offer the best price and value here by carrying containers in double-stack well wagons to maximise train capacity.

More long-established trailer on flat car (TOFC) or piggyback traffic continues to shrink, and TOFC is now less than 10% of intermodal volume. North America’s railways have not yet figured out how to grow the TOFC business by improving the efficiency of the wagons used to carry road semi-trailers. There are some more efficient European designs, but they are frankly too expensive per platform size relative to the well wagons.

Table 1 breaks down composite low to high volume range predictions for selected commodities. If the war in Ukraine continues, we should expect shortages of specific commodities to increase rail freight demand, particularly for grain, but the conflict and its impact on global demand and supply is the obvious wild card in this analysis.

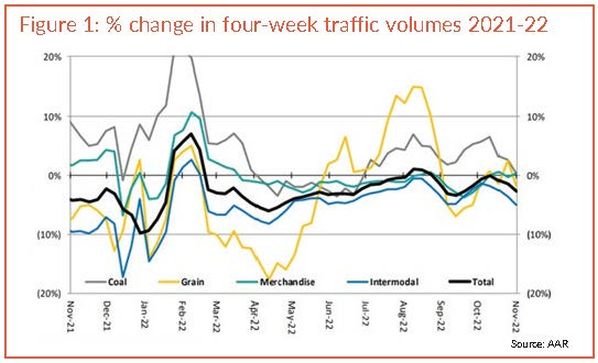

How traffic can vary over the course of one year is shown by Figure 1 (see below), which plots the monthly year-on-year change in total volume and in four commodity groups. This seemingly random pattern suggests just how challenging forecasting can be unless it is broken down by market segments.

Focus on investment

A second approach is to focus on what pressure is being applied to railway asset bases, and how railways are investing in rolling stock and infrastructure to meet the demands that changes in freight traffic are placing on them.

In 2023 I believe that there will be a continued emphasis on spending to maintain the health of physical assets such as mainline track. Specific budgets and details of the scope and location of projects were due to be released by the Class 1 railways in early January, and I would expect materials budgets to be between 8% and 10% higher due to inflation. The amount of work to be undertaken to maintain and renew sleepers, ballast and rail is likely to be close to the volumes seen in 2022.

Turning to rolling stock, there are just over 1.6 million wagons registered for use on the North American network and we might expect the continuing fleet replacement rate to be close to between 40,000 and 45,000 units a year. Historically, there is a large variance from year-to-year in the Capex fleet replacement rate, and we have been below the average rate for two years now. I would therefore expect that at some point in 2023 we should see a recovery towards or just above the average replacement level. But this might not be true for certain wagon types, reflecting traffic trends, and I would expect low replacement rates for intermodal wagons as well as hoppers to carry coal and sand. There will be normal to higher build rates for tank wagons to carry chemicals and for grain hoppers.

At some point soon, but not yet, a significant increase in intermodal market volume - possibly above twice that of real GDP as NS suggests, or 4.5% to near 6% - is going to require many more intermodal platform wagons.

Another wild card enters the game here, namely the use of telematics and GPS-equipped wagons to improve fleet usage. This could benefit the wagon owner or user with an increase of between 8% and 30% in the number of trips made by the vehicle each year. Better and more reliable wagon use will either reduce the required fleet size by customer and by wagon type, or possibly increase market demand from shippers for what might finally be a more reliable service, delivering consignments on schedule.

The economic benefits and impact on fleet size are likely to dominate business cases for telematics over the next three years, so you might expect wagon leasing companies and their clients to hedge their bets until the outcome from adopting telematics becomes clearer. My prediction is that the early digital innovators will take the plunge by summer 2023, with those who like to be second following their lead by late 2025. I also expect to see many business case presentations this year setting out how GPS can enhance the added value of wagons fitted with this technology. Potential adopters I have spoken to are hungry for such value-added intelligence to guide the resizing of their fleets.

For locomotive fleet investment in 2023, it would appear that the combination of recent new orders and rebuilt locomotives will be sufficient to haul expected traffic over the next 12 months. The total number of new diesel locomotives that will be ordered is likely to be less than 150, but that total will become clearer by early March. I do see some selective orders for new battery-assisted or hybrid locomotives actually being built and delivered during the next 18 months. However, these would be prototypes mostly designed to test the market and durability.

The third approach to forecasting future freight volumes is to identify the challenges, and potential opportunities, that are limiting rail’s ability to attract new customers and retain existing shippers.

As we start 2023, the global energy and food crisis should be providing plenty of business for the freight railways, as these are bulk products moved in bulk where the economics favour rail over road. So what is going wrong? There are a few obstacles to progress. The first is less focus on a strict return to cost reduction precision scheduled freight operations with NS exemplifying the changes underway at some of the Class 1s.

The main stumbling block appears to be a continuing shortage of drivers and other train crew. Too many were laid off over the past two years, and too few rehired or recruited from new and then fully trained.

Like many American industries, railway human resources departments did not get the memo about demographic trends and likely worker shortages, and have tended to ignore the preference for a better quality of life among today’s replacement generation. It might take a year or two for railway employment to fully stabilise at a level with a sufficient labour pool in reserve to cope with spikes in demand. However, I expect these labour issues to eventually be resolved.

In contrast, locomotive shortages should not be a barrier to volume growth. There are plenty of locomotives currently in storage that could be rebuilt to extend their service life, and the two major North America manufacturers have sufficient factory capacity to build new locomotives if this is the preferred option. Throughout most of 2023 and into 2024, it appears that buyers and vendors will mostly satisfy power requirements by modernising older but still safe locomotive underframes, replacing dc traction equipment with ac drives.

There are clear market opportunities for moving liquified natural gas (LNG) by the trainload at very low temperatures using cryogenic tank wagons. However, the regulatory review is slow, for reasons that remain a commercial mystery. Given sufficient will, this delay could be resolved, but I suggest not in time to make a difference to rail in 2023. After the safety review is completed, it will take time to build LNG tank wagons to the new specifications, with the earliest delivery date likely late 2024.

There are clear market opportunities for moving liquified natural gas (LNG) by the trainload at very low temperatures using cryogenic tank wagons.

Another opportunity is the rebuilding and modernisation of the electrical power grid in the United States, including its generators and substations, but making more use of rail here remains a concept plan at best. One issue is the lack of an integrated national plan for improving clearances on the rail network, and specifically to increase the maximum loading gauge. Maximum widths are fixed at between 3.35m and 3.96m, and there is no strategic railway routing map indicating which lines can accommodate modern and more efficient power generation and distribution equipment which falls within the 4.27m to 4.88m envelope. We have been stuck with this comparatively narrow loading gauge since the end of World War II, including on routes used by strategic military and industrial traffic, while the maximum height and gross weight of freight trains have both improved significantly across North America.

Improving clearances to accommodate wider loads would probably cost up to twice as much as the recent $US 6-10bn programme to modernise the Panama Canal for bigger ships. Such expenditure is unlikely until later this decade even if a plan were adopted this year. And before any work begins, the projected market demand would need to be thoroughly worked out and a way found to earn a return on necessary long-term capital expenditure.

Is intermodal the answer?

Intermodal is perhaps most frequently identified as a potential game-changer for growing freight by rail. Taking NS as a case study of recent performance, intermodal appears to be in somewhat robust health, at least on a selective basis and by geographic corridor. NS has been gradually replacing its diversified wagonload traffic base with more intermodal units, and at the end of 2022 some projections put intermodal traffic at near to 50% or more of total NS revenue units.

There has been a significant change in traffic segments towards intermodal over the past two decades. It is not yet known outside NS how profitable intermodal is as a separate operating division, but we do know that NS has a good network made up of carefully-selected strategic lanes that have a high density of intermodal movement volumes. These high traffic density networks should enable intermodal to cover its fully allocated costs as a separate business unit.

The railways in all three North American countries do have to improve the reliability of their service delivery if they expect to gain customers and take market share.

The wagonload business has traditionally contributed to NS’ profitability, but since 2007 the railway has faced serious challenges. Profit may have declined by as much as 25% over the past 15 years largely from the loss of coal traffic from the Appalachian region. Intermodal may be the only solution to recovering growth lost from the wagonload business, but it depends on how profitable it can be when it has to carry its share of the company’s total fixed and variable costs on a fully allocated basis.

That question is still being examined, but I remain cautiously optimistic about the future of intermodal in North America. That is because it is being carefully pursued as a commercial opportunity that integrates engineering with economics. The engineering side of me expects some breakthroughs that will bring more customers to rail, but not necessarily in 2023.

While storm clouds on the horizon suggest an upcoming recession in the US, this is not absolutely clear. The nation has a strong, diversified economy and is rich in many natural resources including oil and gas, while climate and geography are favourable to agricultural production. The population base is well educated and diverse with a wide range of practical skills, although we do face an employee shortage in some critical areas.

Despite some deferred maintenance, the US has a fairly balanced and functional surface transport network. The engineering industry score cards for the rail freight network across the US and Canada show it to be in above-average physical condition when compared with some taxpayer-funded infrastructure such as road bridges and highways. The rates charged by private freight railways are competitive and reasonable when compared with many freight operators in the public sector elsewhere. Mexico has two competing freight concessionaires that are doing well at growing their business without government subsidy.

The railways in all three North American countries do have to improve the reliability of their service delivery if they expect to gain customers and take market share. Most senior railway managers and their boards of directors know this, and there is no argument against the need to improve. The challenge is how to do it and I would say a rapid breakthrough this year is unlikely.