IN recent years, China’s metro systems have facilitated strong economic growth and played a vital role in the country’s shift to urbanisation. The metro systems have improved the quality and efficiency of urban public transport, relieved congestion, and also optimised the urban environment.

Metro systems in Chinese cities have grown exponentially, with over 100 lines opening within the past decade. The combined length of urban rail trackage was over 5000km by the end of 2017, and Shanghai now boasts the largest metro network in the world at more than 640km.

However, China has reached a new stage in its development, which will profoundly affect population distribution, the economy and investment.

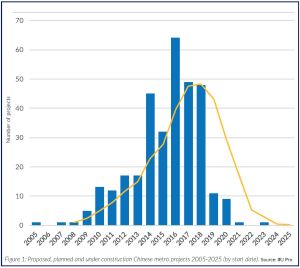

Figure 1 displays the number of metro and light rail lines which began construction or are planned or proposed to start construction between 2005 and 2025. As Figure 1 illustrates, China has witnessed rapid growth in the sector, with the graph showing similarities to a financial bubble.

In mid-July, China’s General Office of State Council issued its “Opinions on Further Strengthening the Management of Urban Rail Transit Planning and Construction.” This new policy replaces guidelines and parameters which were first put in place in 2003, and emphasises reducing debt and commercial risk levels.

China’s metro systems play a critical role in urban development, and in turn require a high level of support from both regional and central governments. The new policy aligns with China’s efforts to limit the liabilities of regional governments and control infrastructure spending.

In the broader context this is part of China’s policy of deleveraging. Moody’s Investor Service has rated the new policy as A1 stable, stating that the policy on metro construction is positive for the long-term development of the sector. The new policy can be broken down into four main components:

- Minimum threshold: In relation to the application of metro construction, the minimum threshold of a city’s fiscal revenue and regional GDP has increased three-fold from Yuan 10bn ($US 1.45bn) and Yuan 100bn to Yuan 30bn and Yuan 300bn respectively. The minimum threshold for the construction of light rail has also more than doubled, from Yuan 6bn to Yuan 15bn in fiscal revenue and Yuan 60bn to Yuan 150bn in regional GDP. As for the scientific nature of urban rail planning, the initial passenger transport intensity of newly-proposed metro lines cannot be less than 700,000 people per kilometre per day and less than 400,000 for light rail. This represents a drastic change from the former policy which did not specify minimum ridership. The population requirements of 3 million have been redefined to the urban resident population who live permanently in the metropolitan area.

- Investment criteria: The policy promotes diversified funding sources for both companies and regional governments with the aim of attracting private sector investment. Project bonds, hybrid instruments and securitisation will be used to encourage investment. Investment scales have been capped, and the new requirements state that the cost per kilometre of a network must not exceed Yuan 600m, and total investment in a project must be no lower than 40%. It is now strictly forbidden for cities to use public-private partnerships (PPP), and other forms of “disguised debt” for the construction of projects. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) now controls the debt risks for new projects.

- Cooperation between departments: The new policy emphasises the need for better coordination and supervision mechanisms between governmental departments. One of the ways this will be attained is through the creation of shared databases, between the NDRC, the Ministry of Housing, the Ministry of Urban-Rural Development and other relevant departments. It is expected to improve the level of supervision and project planning effectiveness. Relevant departments of the State Council will strengthen and oversee planning and guidance for construction, while relevant regional departments will be responsible for the supervision of the whole construction process, with urban government taking the main responsibilities for debt risk.

- Planning standardisation: The Regional Development and Reform Commission will conduct a preliminary examination with the regional level housing construction department before the plan is submitted to the state. The two layers of planning will then be reviewed for approval by the NDRC and the Ministry of Housing and reported to the state for filing.

The companies which pass the new policy will receive benefits, as regional governments will be required to provide transparent funding and active support for projects. Risk will also be decreased for the companies which pass as projects will no longer be built on bad debt. If a project’s debt financing does not match up with the new requirements or fails to meet the appropriate debt repayment structuring, the project will not be approved or will have to be cancelled. If enterprises are too highly leveraged, effective measures will be taken to reduce debts and the construction of new projects will be suspended.

As the minimum threshold for construction has been raised three times, many cities that previously met the policy criteria will now be excluded.

Currently, out of the 43 cities that have state-approved metro construction projects, it is estimated that around a third fail to meet the new requirements. This includes Nanning, Urumqi, Hohhot, Baotou, Kunming, Xi’an, Lanzhou, Shenyang, Harbin and Guiyang.

Despite a large urban population of over 2.5 million people and a regional GDP of Yuan 274bn in 2017, Urumqi fails to meet the new strict requirements. The city of Lanzhou also falls short with a population of 3.6 million and GDP of Yuan 252bn as does Nantong, which has a population of 7.3 million and an urban resident population of 1.9 million, and Luoyang with a population of 6.5 million of which 1.8 million are urban.

China’s National Bureau of Statistics published the top 100 cities GDP list at the beginning of the year. A total of 76 cities meet the GDP requirements of Yuan 300bn, leaving 592 cities that do not meet the criteria. The remaining 24 cities on the list account for over 120 million people who will be without metro access for the foreseeable future.

Large scale infrastructure spending and urbanisation have long been in China’s growth arsenal. Although effective at stimulating economic growth in the short to medium term, they can also bring long-term side effects.

Metro construction is expensive and typically costs Yuan 600m to Yuan 700m per kilometre. Such investment can become unsustainable in cities with insufficient financial capacity, population size and economic aggregate, leaving a financial black hole producing poor returns and fruitless results. This puts long-term pressure on local economic development, and leaves the state and engineering contractors as the main beneficiaries.

The new policy is likely to mean that cities which are earlier in the development process fail to meet the new parameters and enter a negative growth cycle of population reduction and shrinking investment. However, the policy is expected to facilitate further growth in major cities like Shanghai, Shenzhen and Chengdu, which already possess metro networks, strengthening their grip on Chinese urbanisation.

To gain access to data for over 2200 global projects and over 1400 fleet orders, subscribe to IRJ Pro at www.irjpro.com